Ever saw a skeleton in a museum? Well, in the museums, the bones must have looked dry and crumbly but in your body, trust me, they are completely different. So, let’s take a look at the very much alive bones!

The Axial Bones

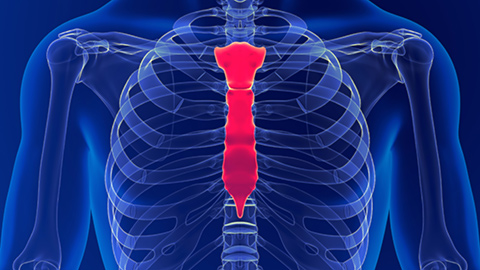

The Sternum:

The breastbone or sternum looks like a dagger pointing downward. To the “handle” of the dagger is hinged the narrower “blade”, consisting of four fused segments. The tip or point of the dagger consists of cartilage in youth but becomes bony in middle life.

The cartilages of the first seven ribs are attached to the sides of the sternum: the two clavicles or collarbones are joined to its upper part. The wide “handle” of the sternum protects the great blood vessels diverging from the heart. The “blade” and the adjacent rib cartilages guard the heart itself.

The Skull:

The last groups of axial bones are those making up the bony skeleton of the head and face. There are twenty-two bones in the skull, twenty-one of them so firmly united that movement between them is impossible. One bone, the mandible, or lower jaw, is hinged to the rest of the skull just in front of the ear opening and is independent and movable.

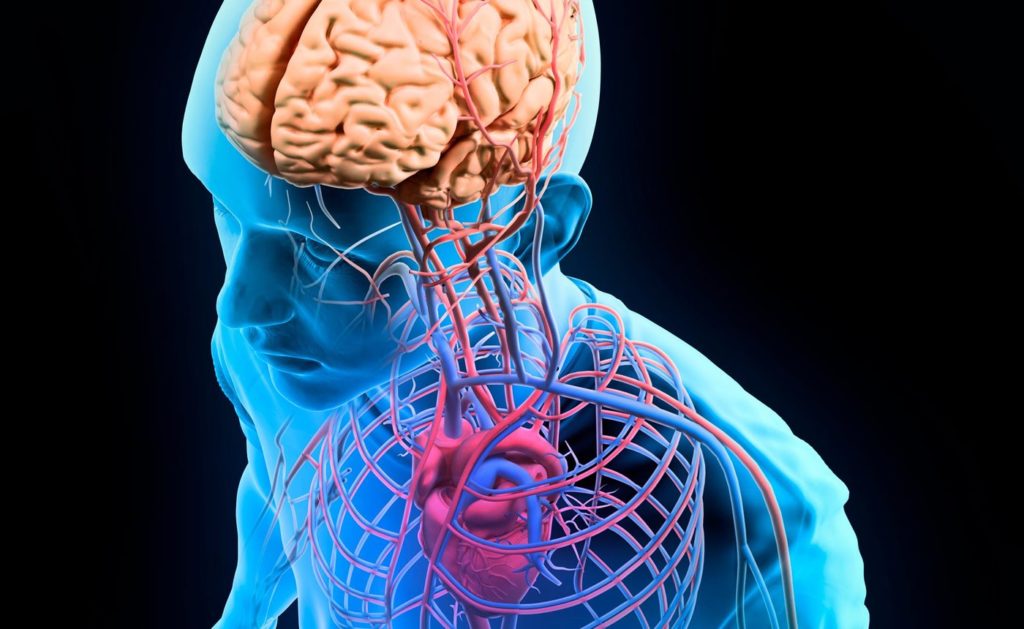

The skull is conveniently divided into two parts: the brain box (case) or cranial cavity and the bones of the face. In some lower animals, such as fishes or rabbits, the brain box is small and relatively insignificant. It lies behind the face, which projecting forward is very prominent. The brain box in man has expanded to such an extent that if we look at a human skull from above, no part of the face is visible. The forward expansion of the brain box has resulted in very deep sockets for the eyes. In lower animals, the sockets are quite shallow and the eye is less protected than the human eye.

The walls, roof (vault) and back part of the floor of the brain box are formed by six curved plates of bone whose saw-tooth edges fit into one another like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. At birth, these edges are not yet interlocked and that is why there are soft spots called fontanelles on the head of a newborn baby. The floor of the brain box is high in front, coming above the eyes, but it slopes rapidly downward. At its lowest point, some distance forward from the back of the head, there is a great hole called appropriately enough, the foramen magnum. Through it passes the spinal cord, as well as various arteries and nerves.

The Hyoid Bone:

In the angle where the floor of the mouth meets the neck is a slender U-shaped bone known as the hyoid bone. “Hyoid” means “upsilon-shaped” in Greek and the hyoid bone is so-called because the corresponding bone in animals with a forward-pointing snout looks something like upsilon. Ligaments suspend the hyoid bone from the skull and from the bone, there hangs the Adam’s apple or thyroid cartilage. This is the chief cartilage of the larynx (voice box). In swallowing, the larynx is pulled up to the hyoid bone.

The Appendicular Bones

The Clavicle:

The clavicle, or collarbone, is a slightly curved horizontal structure and it gets its name from its resemblance to a type of key comment in ancient Rome. At its inner end, the clavicle is united to the breastbone and at its outer end, about an inch from the point of the shoulder, it is attached to the shoulder blade. The clavicle is really a horizontal strut, forcing the shoulder joint to keep its distance from the breastbone no matter how varied its movements. The swing of the clavicles can be felt when the shoulders are shrugged, depressed, brought forward or thrown backward. When the collarbone breaks, the shoulder collapses inward and these movements are no longer possible.

There is still so much more to learn about the Appendicular Bones. So, please share your comments and don’t forget to come back for part 4.