Sepsis is a generalized infection caused by bacteria. It causes significant inflammation. The disease has been known for a long time since sepsis was coined in 1837. The word sepsis is still widely used by the general public and physicians. Today, infectious diseases specialists tend to replace the term sepsis with “bacteremia associated with sepsis” (bacteremia meaning “circulation of bacteria in the blood” and sepsis “generalized inflammatory response, following a serious infection”).

– Bacteremia is defined as the presence of bacteria in the bloodstream. When their number is low, they are eliminated by the body’s defenses, which is the most common situation. In this case, the person has no symptoms but may experience a slight fever (feverishness) or transient fatigue. When the bacteria are too numerous, or the person’s immune system is weakened (by treatment, illness, HIV infection, or congenital immune deficiency), or overwhelmed by their numbers, the body can no longer eliminate them, leading to sepsis.

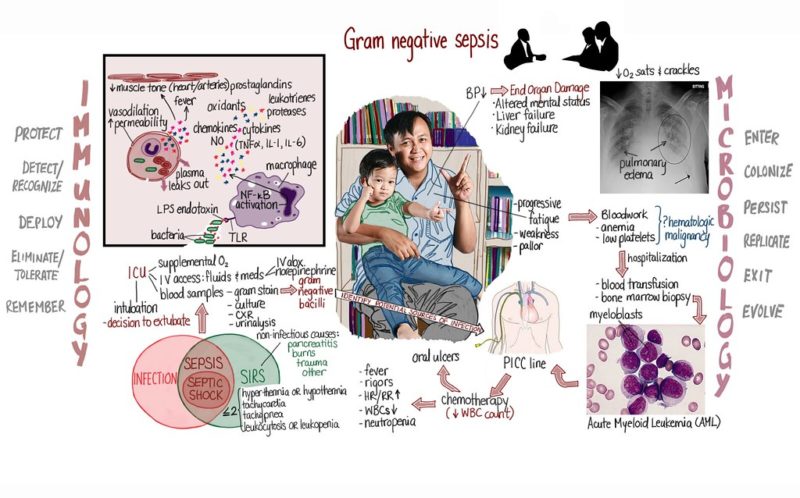

– Sepsis is the excessive generalized inflammatory reaction in response to a severe infection.

– Septic shock (which can also occur in sepsis) is related to the release of toxins secreted by certain bacteria into the bloodstream.

Causes of sepsis

The release of bacteria into the bloodstream can be linked to situations that are sometimes bland, such as brushing teeth, dental care, or rarer conditions such as cleaning a wound, changing a catheter, a surgical procedure, or even a pulmonary, urinary, osteoarticular, digestive (particularly in the bile ducts), skin (infected wounds, abscesses or bedsores) or endocarditis (infection of a pathological heart valve) infection, etc.

The risk of sepsis is increased by the presence of a “foreign body” in the body, such as a bone or joint prosthesis, a heart valve prosthesis, a vascular catheter, a urinary or digestive catheter, a tracheal intubation catheter (catheter allowing air to enter the bronchi).

Bacteria that accumulate on this foreign material or an infectious site are released episodically into the bloodstream.

All bacteria can be involved, including those not pathogenic (i.e., do not usually cause infection), and are generally carried by the body in the skin, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract.

Fungi, such as candida, can, but rarely, cause septicemia, which is then called fungemia, essentially in people whose immune system is deficient.

Risks of septicemia

People at risk

People whose immune system is weakened are particularly exposed:

– women who have just given birth (sepsis is then called puerperal fever) and newborns. Sepsis is a significant cause of birth mortality in emerging countries.

– the elderly.

– people with diseases that reduce immunity, such as diabetes, cirrhosis, certain cancers or hemophilias (blood cancers), HIV-AIDS, and congenital immune deficiencies.

– drugs or treatments that may weaken immunity, such as corticosteroids, certain chemotherapies, or biotherapies.

– people in hospital are exposed to the risk of septicemia with nosocomial germs, often resistant to antibiotics

Risk factors

The risk factors are:

– drug injections with contaminated equipment or without skin disinfection

– wearing osteoarticular prostheses, urinary, digestive, and intubation tubes, drains, and catheters

– valvulopathies (heart valve diseases) or prosthetic valves (heart valve prostheses).

– skin infections: furuncles, bedsores, burns, wounds.

– dental, sinus, and biliary infections, etc.

– surgical interventions.

Symptoms of sepsis

Sepsis is a generalized infection responsible for a high fever but sometimes a drop in body temperature (hypothermia), significant fatigue, often associated with an acceleration of the heart and respiratory rates. It is accompanied by chills, sweating, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and even mental confusion in older and younger people. Fever, chills, and sweating often occur in bouts.

Other signs vary depending on the site of the initial infection and complications. Sepsis may be complicated by “septic shock,” with a drop in blood pressure and impaired function of various organs due to lack of blood supply. When the blood supply of oxygen is insufficient, the skin becomes cold, mottled, cyanotic (bluish), especially on the extremities.

Diagnosis

During a blood test:

– On the blood count, the white blood cell count is usually very high or, on the contrary, significantly lower.

– The CRP (C-reactive protein) and procalcitonin levels in the blood indicate the existence of inflammation, but their elevation is not specific to an infection. However, low levels make it unlikely that sepsis is present.

– Bacteremia is detected on a blood sample that shows bacteria in the blood, sometimes visible on direct examination under a microscope. The blood sample is cultured (hence the term “blood culture”) to identify the bacteria responsible and determine their sensitivity to various antibiotics. Ideally, a blood culture should be done as soon as bacteremia is suspected before any antibiotics are taken, skewing the results. This is not always done and complicates the interpretation of results. Other samples are taken from potential entry points of the infection (sputum, urine, catheter, probe, wounds) to identify the bacteria and put them in culture.

Other radiological, biological, or cardiological examinations are requested to search for the initial site of infection and secondary infectious locations and evaluate the severity of the disease and shock and their impact on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in particular.

Prevention and treatment

Sepsis is a severe disease, with a risk of death, especially in the case of septic shock, complications of initial or secondary infections, and damage to “noble” organs that may leave sequelae after the illness has healed.

The risk of complications depends on the person’s fragility, the speed of treatment, and the existence of antibiotic resistance.

Emergency consultation is necessary when signs of infection persist despite antibiotic treatment, especially if the person is vulnerable, has valvulopathy, or carries foreign material.

Prevention of sepsis

People at risk because of a lack of immunity or wearing a joint or valve prosthesis should receive preventive antibiotic treatment before specific dental or medical/surgical procedures.

To ensure the complete healing of an infectious outbreak and avoid the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, it is essential to respect the doses and duration of treatment and to take antibiotics only if necessary and then to take them for the period recommended by the doctor.

Treatment of sepsis

Treatment is carried out in a hospital, usually in intensive care units or intensive care units.

The treatment of the infection is based on intravenous antibiotics, started as soon as possible after the blood cultures but without waiting for their results. A combination of 2 or 3 antibiotics is usually used, depending on the presumed origin of the initial infection, the patient’s condition, and the existence of other pathologies. The results of the blood cultures are obtained in 1 to 3 days, depending on the germ, and allow the antibiotics to be adapted. The duration of antibiotic therapy is 7 to 14 days or more, depending on the negativeness of the blood cultures, the clinical condition, the fever, the germ, and the initial and secondary localizations.

The material on which the bacteria may have settled, such as a catheter, must be removed, open wounds thoroughly cleaned, and abscesses drained.

Treatment of vital functions

The management and monitoring of the cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal systems generally lead to the infusion of intravenous fluids to combat shock, restore normal blood pressure, and provide oxygen. In severe cases, good ventilation must be ensured by intubation or even a breathing machine.

Injectable corticosteroids are prescribed in some cases when blood pressure remains low despite treatment.

The number of sepsis increases because we live older and longer with pathologies like diabetes, cancers, HIV-AIDS, etc. Sepsis is a severe pathology. Its management has improved thanks to progress in resuscitation and antibiotics. Still, we are now faced with bacteria that have become increasingly resistant to antibiotics after years of neglect, while there is a lack of new antibiotics. We all have a role to play, individually and collectively, in the fight against antibiotic resistance by restricting their use to well-established indications and carefully following the doses and duration of treatment.